If you’ve spent any time looking at oaks in the Willamette Valley, oak galls will be on your list to look up in a field guide. And, yes, there is a field guide for that!

Category Archives: wildlife in the PNW

A few Thoughts About Snags Part I

Biological richness of snags and logs

Dead trees equal higher biological diversity

Opening in the lower surface of mature polypore

X-section of veiled polypore opened to show pore layer inside

Immature fruiting body

Cryptoporus volvatus

Dead tree with marshmallow-sized polypores fruiting on bark

Note the circular beetle entrance hole to the left of emerging fruiting body.

Up Next: Part II – Structural Diversity

Notes

Photos © 2020 Taylor Gardens. All rights reserved. Please request permission if used. No commercial use allowed without prior permission.

Forests and Pollinators

Here in western Oregon we are gifted with many habitats and a variety of native plants for most any growing conditions. Wet soil? Try plants that love the ditches like camas, showy milkweed, or goldenrod. Shade? No problem – forests are full of shade loving shrubs and perennial plants. Gaps in the tree canopy and edges along roads or meadows are sunnier and packed with resources that increase habitat resilience and biodiversity.

Marginal land like ditches, roadsides, and rights-of-way might sound useless, but they are anything but that. Just check them and see how mosses, plants and animals take advantage of them. “Marginal” can mean not the greatest, or alongside. Land alongside roads, tracks, fields and power lines make up a tremendous amount of acreage.

Pollinators require nectar and pollen resources, but equally important is the availability of protected overwintering sites like leaf litter, large ferns, and tree cavities. Undisturbed forests, and even timber farms provide these in abundance when managed properly by leaving or adding plants that are often classed as non-timber resources. You might not be able to sell them, but they will enrich your forest in many hidden ways.

Agriculture and development daily gobble up land that was previously uncultivated or unnoticed, and that reduces refugia for native plants and animals. An example: unsprayed roadsides are one of the places milkweed can flourish unmolested to give monarch butterflies a chance to lay eggs and fuel up on nectar. Milkweeds, in fact, are some of the most prolific producers of nectar for lots of other pollinators too.

Oregon grape, vine maple, cascara, Nootka rose, Pacific ninebark, salal, spiraea and ocean spray are all common forest shrubs that provide superior habitat for pollinators. If your forest is lacking in diversity, you can plant these species either in the understory or along forest edges. If you have open spaces, you may even want to consider planting “pollinator patches” of native flowers, such as lupine, meadowfoam, clarkia, selfheal, goldenrod and aster. Many of our common forest plants, and indeed our food supply, may depend on this kind of proactive conservation work!

Kirk Hanson, Forestry Director

Northwest Natural Resource Group

One advantage to growing forest-adapted shrubs, wildflowers and trees is early season nectar. The ethereal white flowers of Osoberry (Oemleria cerasiformis) appear against the green forest background as early as January. Tall Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium) may accompany red flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum) to dramatic effect. The dense creamy sprays of goatsbeard (Aruncus dioicus) on shady edges attract multiple species of native bees.

Late season nectar is often scarce because our hot, dry summers force most plants to get their reproducing done early. Summer dormancy is a survival strategy that produces yellow leaves on perfectly normal osoberry late in the season. However, goldenrod (Solidago spp. and Euthamia occidentalis), Aster spp, and rabbitbrush (Ericameria sp.) are used extensively by insects late in the season. With a little moisture, some perennials will even bloom a second time.

Pollinators aren’t the only beneficiaries of wise planting. Birds, mammals, and predators all use the fruits, structures, and protection that a diverse forest provides. Lower levels of pests and higher soil moisture and fertility are a few of the by-products for landowners and farmers.

Of course an equally powerful way to protect wildlife and pollinators is to reduce or eliminate agricultural chemicals on your property. Properly using those you need, in small quantities, and with great care with respect to timing of application is essential. If you live in Yamhill County, join the Yamhill Butterfly Gardeners, the Native Plant Society, or get in touch with Taylor Gardens for a consult to explore your options.

-Photo: Sonya Wilkerson

-photo:Wikipedia.org

I speak for the bees

(note: if you receive this post by email you may need to go to the post on WordPress to see all content)

It’s no secret that bees are having a hard time lately.

If the image of a honey bee just popped into your head, you would not be alone. Domesticated and brought here in the 1600’s, honey bees are iconic. They have been our civilized companions for centuries. They tolerate being carted around from place to place, and of course, there’s the honey. However, honey bees are not native to North America, and they are not even the best pollinators!

Native bees do not make honey, they mostly do not live in large colonies, but they are great pollinators. Their diversity is phenomenal: in Oregon (a hotspot of bee diversity) there are at least 500 different native species! Let’s take a look at these fabulous creatures that live here with us.

Our state’s diverse geography contributes to higher native bee diversity than many parts of the U.S. But 500 species may not be all the bees we have! It turns out, entomologists’ knowledge of Oregon’s native bees is based largely on documented collections from only four sampling sites in the state. Enter the Oregon Bee Atlas.

In a fortunate moment for science, the current Farm Bill included funding for the study of native bees, and one goal in a larger project is to train up citizen scientist teams to collect bees and data throughout the season, for four years, to find out how many and which bees are here. This will help experts assess the health and changes taking place in their populations in this critical time of species extinctions and adaptation to climate change.

I am on one of two teams in my county, and our sampling site is our property here in Gopher Valley. I am super excited to have the opportunity to contribute to this important work, which enhances all our conservation work while making a contribution to science and bees. My friend Emily Gladhart has the other site at Winter’s Hill Vineyard which has a fantastic native plant garden and oak woodland.

Why bees are important

Pollination is the first step in fertilization. Pollination occurs when a pollen grain is deposited on a plant’s stigma – the female plant part. Fertilization occurs when the pollen grain germinates and grows a pollen tube down inside the style to deliver sperm to unite with the ovule. That is the beginning of a seed.

Copyright© 2010 by P. Pearle, K. Bart, D. Bilderback, B. Collett, D. Newman, S. Samuels Accessed 4.2018 at http://physerver.hamilton.edu/Research/Brownian/index.html

Bees pollinate crops. But biodiversity is also a critical part of the story. Native plants support whole ecosystems and rely on pollinators for seed production. Bees move pollen (genes) and increase genetic diversity. Some bees specialize on certain plants, and without their pollinators those plants can’t reproduce. Other bees are generalists. Some generalists (like honey bees or orchard mason bees) can be managed to pollinate commercial crops. Those that don’t lend themselves to such management can be encouraged to nest near crops by providing good habitat, which is like raising your own crop of bees along with your plant crop.

Native bees are food for nest parasites, birds, spiders, and other creatures that can use the protein-packed snacks of bee larvae, pollen, and bee bodies that help make the world go around. These hangers-on are not necessarily a detriment. They are part of the food web and have co-evolved with their hosts and prey.

Native bees live unique lives

The nests of native bees vary by species, but many are solitary, gregarious, or semi-social. Some species are completely solitary. Others nest in a group but still maintain their individual nests. There are species that live in a communal nest; bumblebees have a nest with division of labor (workers, queen). A typical life cycle involves

1. An overwintering stage. Bumblebee queens overwinter alone, wake up in the spring and start foraging to provide pollen for their eggs.

Solitary bees emerge from cocoons where they have been pupating or overwintering as immature adults. They chew their way out of their nest cells.

2. Reproductive stage. Bumblebee queens lay eggs to start their nests. When enough eggs hatch, the queen switches to egg-laying only and lets others take over the tending and foraging duties. New bumble bee queens then mate at the end of the season, the old queen will die and the new queens will find new nests in which to spend the winter.

Solitary bees mate on emergence in Spring, and begin building nests with cells containing one egg and a food packet (pollen loaf) in each cell for the larva that hatches.

3. Nest activity: bumble bees live in larger cavities such as rodent holes or inside trees or buildings, because they need space for the group nest.

Other bees may have nests inside twigs, soil, or cavities, composed of individual chambers for each egg and pollen loaf package. They deposit an egg on the pollen ball and close up the cell (generalized illustrations below), never to see their offspring. Some bees line their nests with leaves, cut in neat circles from plants. Bee nests are varied, amazing, and species-specific.

Illustrations by Steve Buchanan from Bee Basics:An Introduction to Our Native Bees USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership

Clearly, protecting bee nests is a big part of conserving the mind-boggling number of bees we have.

The easiest way to do this is to:

- provide undisturbed areas for bees to excavate for soil nests

- maintain cavities in rocks or wood, and have softer pithy dead stems for them to excavate (elderberry, blackberry and other canes, roses, wildflowers, etc).

- there should be a concentrated source of food, such as blocks of flowering plants throughout the season.

- pesticides are a particular danger to bees, so using none is best; there are less-toxic pesticides, and application guidelines are available to minimize the effect on bees. There is information on alternatives at the Oregon Dept of Agriculture website here: http://www.oregon.gov/ODA/programs/Pesticides/Pages/PollinatorIssues.aspx

In no case should neonicotinoid pesticides be used or tolerated in nursery stock. Be sure to ask your nursery if they can certify that their wholesalers do not use these persistent, deadly chemicals when they grow plants. More info available here, for landscapers, gardeners and foresters.

A hedgerow is an excellent way to build a successful bee haven.

Here are a few scenes from our collecting project so far. It has been cold this spring, and blooms are a bit scarce, so it’s a slow start but weather effects are also important to document. It’s a long game, and data gathered over years or decades will show important trends. Click for more info below.

Some action shots from our collecting activities:

https://www.facebook.com/TaylorGardens/posts/1753753841314691

A special thanks to Ed Sullivan for his photo of the Ceratina bee featured in this post’s header and gallery above. See more of his work at https://www.flickr.com/photos/canoebait

Links to additional information

https://www.arboretumfoundation.org/getting-to-know-our-native-bees/ A great article on all the important things about PNW native bees.

https://xerces.org/pollinator-conservation/plant-lists/pollinator-plants-maritime-northwest-region/ Fact sheet on native plants for pollinators in maritime PNW

https://xerces.org/fact-sheets/ A page of fact sheets. For clarity and brevity I recommend 4 Principles to Help Bees and Butterflies

A look back: The year and a decade in review

2017 marks a decade since we started our conservation projects in earnest.

How timely then, that we were scheduled for a review by the Forest Stewardship Council. The FSC logo you see on your recycled and green wood products indicates the product has been certified to actually be “green”. Members adhere to specific standards that make their forests more planet-friendly. An agency – in our case, the Northwest Natural Resource Group – holds the certificate for its members, shepherds us along, and makes sure we report pesticide use and generally keep to the righteous path. Every few years the FSC audits a portion of the properties that are members of NNRG. This year we were asked to compare current practices to our management plan and explain how we measure our progress. Short answer: mainly by looking, because our “crop” is conservation, so it’s pretty simple compared to an actual tree farm.

It was helpful to look back and see where we are. The original plan was to restore oak savanna and woodland throughout the property. Some areas needed to be logged, others could be sheared and mowed. We have stuck with projects laid out by the Conservation District which differ from the management plan done by a consultant because some of the steeper areas are just too difficult or expensive to access.

Below, a few reflections, photos and assessments.

Progress is incremental. Everything takes time. We will get the scotch broom corralled eventually. Some increments that I appreciate are:

The savanna (really almost a bald) is still savanna-like. Scotch broom was as tall as the tractor when we started but thin soil and hot exposure have slowed down growth.

In all parts of the property, legacy patches of native wildflowers continue to expand and I enjoy finding the odd new plant or population, which gives me great hope, even though there will always be weeds and non natives.

The woodland oaks have more space and continue to put on growth after being crowded for many years. These things are best seen in contrast with previous condition.

Maintenance is forever. Yes, it is. Scotch broom is not forever, but it seems like it.

Getting new stuff to grow is a challenge, but Roemer’s fescue has really been a friend. California oat grass was hanging on when we arrived, we’ve seeded more of it and it’s a lovely bunch grass.

In the absence of fire, a good mowing makes everything better. I would like to burn more. but we don’t have fire available for management (land area too small, too close to neighbors, too expensive, etc), so we must pick our battles and do what we can.

Early- or mid-summer is the best time to mow for our objectives, because this often will kill mature scotch broom. But it is difficult to find a mower operator who will do this when we need it. Tom’s walk-behind has been a great help to reduce the non-native grass thatch in many places and a get to some of the broom in a timely fashion after the natives are done blooming.

Some firs have died of drought in the last few years – a sign that they are not suited to this site and/or climate change in this location. Possibly the thinning took away some of their support system.

Douglas fir dying from the top down from repeated drought

Trees that were girdled to make space in the Land of Moose and Squirrel are toppling over but the big snags live on, with their tufts of branches still green, for now. The plan was to make them last as long as possible and right now they pose little threat to the surrounding oaks while offering a perch and some cavities for birds and squirrels.

Some oaks will unfortunately be on the losing end as conifers outgrow them in the inaccessible areas. On the positive side, our steep slopes provide many niches that are home to a variety of species, and some prefer a mixed forest, or a more closed canopy and patchy landscapes are natural. The thickest scotch broom was even favored by common yellowthroats in past years, although that will not save it from the knife I’m afraid.

Our squirrel survey revealed that western gray squirrels were using some pretty dense vegetation, and we see them in conifers around the house. On moister lower slopes, birds like Pacific slope flycatchers and black-throated gray warblers prefer our damp, cool headwater streams, shaded by a mixed conifer/oak forest that protects the water table and is the source of our springs. Sword ferns and moss carpet the ground. Wilson’s warblers return to their low perches here every year. It is a cool and welcome spot during the longer, hotter summers.

Mixed woodland, young firs will overtop oaks in time. Dead scotch broom in foreground.

Current Projects

In partnership with the Yamhill Soil and Water Conservation DIstrict, we are working to get the broom under control so we can manage it better. The woodland areas have a more benign microclimate and deeper soils than the savanna. Hence more weed invasion. Removing tree cover plus soil disturbance, while beneficial to oaks, has had the predictable result of releasing scotch broom to grow rampantly and outpace our control efforts. Repeated mowing early on kept the broom short, but did not kill it and it rebounded in the last few years. We were able to hire a contractor to spray and mow the worst of it this year.

In one area there are a lot of native plants hiding underneath, including rein orchids. We tried hand cutting and painting first (at my request) to see if we could avoid broadcast spraying. But after a morning of slogging, with the prospect of even taller and denser broom to come, I relented and agreed overspraying was a better choice. Fortunately James, our contractor, was quite careful (he really liked the orchids, which were new to him), and by the time he came back to mow, the orchids and other wildflowers were mostly underground, post-bloom. The wintertime “after” photo below makes me so happy!

Next year we’ll go in for a cleanup to spray regrowth missed on the first pass and make a plan for the seedlings – likely a combination of careful pulling and spraying in the dormant season. One mistake we will not repeat is to keep mowing the broom when it is small, since that just grows bigger roots for growth the next season.

In the third year of the project I plan to spray out non-native grass in several otherwise “clean” areas for a broadcast sowing of native plant seed. Non-native grasses are the second most vexatious problem we have. Burning a few smaller piles of slash works well to pave the way for broadcast sowings of California oat grass and Roemer’s fescue plus wildflowers. Checkermallow (Sidalcea spp) is still germinating from sowings more than a year or two ago, and slowly we are increasing the ratio of native to non native. I will be keeping an eye out, especially in the woodlands for new populations of natives(like the mystery lily below) and hand-weeding life rings around them .

Finally, aside from weeds, one of the challenges in the last few years has been unusually heavy winter rains that scour our small headwater streams. Adjacent land that formerly was covered with forests in various stages of regrowth has been cleared for agriculture, or just cleared and gone to broom. This means rainwater doesn’t get intercepted and soak slowly down to the water table like it used to. A rain drop takes hours, instead of days, to reach the creek across the road. We do what we can to slow it down, but as you can see, there is a large watershed area off the property. Our little paths have undersized culverts where they cross the streams, so the culverts get plugged up.

Again the Conservation District came through to quantify catchment areas and re-size some culverts that will be replaced, to handle the increased water volume. Eye opening views of our hydrology came to light in these maps. Ouch, no wonder there’s such a torrent.

We are slowly making some progress to bring back more native habitat and native plants. The weeds will always be with us, but we continue to make headway and enjoy our animals, birds, and plants through the seasons and the years.

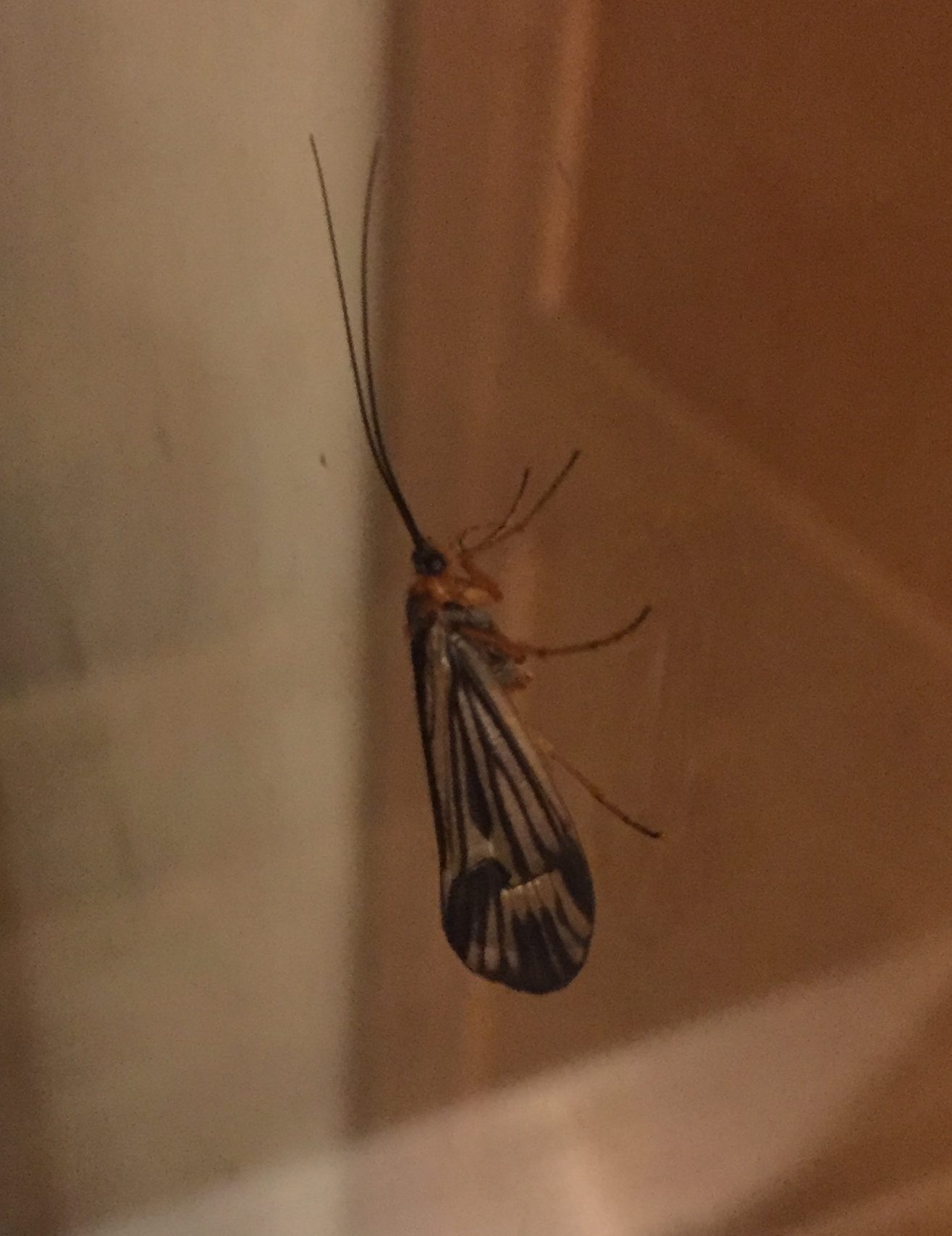

Caddisfly

I did not expect newly emerged winged things to be coming out Oct 31, but here is a caddisfly (Halesochila taylori). One or two came to the house lights. I am still researching their biology. They live in healthy wetlands and near stream and lakes. So, Yay!

I love their elegant antennae and modern-art wing pattern.

Caddisfly adult 10/31/3016 Gopher Valley OR

This trout fishing page has info on life cycle: http://www.troutnut.com/hatch/12/Insect-Trichoptera-Caddisflies

Creature and Blooms update Fall 2016

A quick post to showcase creatures we are enjoying here in Gopher Valley in NW Oregon.

Note: if you get this post by email, the videos will not show up. So try coming to the blog page to read.

Crickets this year are abundant.Their chirps monopolize the bandwidth of evening sound. We have two kinds: the slow-singers and the fast-singers. Perhaps bush and tree varieties. During hot late August and Sept evenings, one highly successful individual got the volume past the point of enjoyment for us mammals indoors.

In this video below you can hear the fast singer competing with the slow guys in the background. Apologies for the low res, but you can get the idea.

Snowy tree cricket or maybe another kind.

Evening primroses (Oenothera sp) are not a native flower, but they bloom their hearts out all spring and summer into fall and the extended color, fragrance and nectar is a gift to insects and humans. Crickets perch on the stems, light evening primrose fragrance is released into the air each night when they open after dusk. Flowers open so quickly you can see the petals move! Easy to grow from abundant seed, too.

A couple of snakes. Some gopher snakes are very tame, but others are aggressive and defensive. I found a baby on the road that gathered all of it’s 6 inches into a compact spring and leaped toward me as I stepped back from taking a photo. This big one we petted as it toured the patio methodically looking into each and every corner for some dinner, and it hardly noticed us.

Adult gopher snake

A rubbery rubber boa. They are usually underneath something.

Rubber boa

Despite the heat, good old Oregon sunshine (Eriophyllum lanatum) came up from winter-sown seed in the hedgerow-in-progress, and bloomed by the end of the summer. Thank you, best native plant friend! And that is narrow-leaf milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis) keeping right up with it. Easier to start this year than the showy milkweed, and still native to our region. Contact me if you would like growing or seed source info.

In Praise of Snags

Snags are standing dead or dying trees. In natural forests in the Pacific Northwest, there are usually a number of trees that have died from lack of light, overcrowding, competition and whatnot. Forests older than 150 years are heading into old growth status and by then some trees in these forests have been killed by fungi infecting the roots or trunk (the diseases they cause go by colorful names like stringy butt rot or laminated root rot). Wind is a big creator of snags. There may be some broken tops in trees with sound roots but weak trunks (windsnap) or if the roots are rotten or the ground soft from rain and snow, blow downs (windthrow).

In an old-growth west side conifer forest (250 – 1000+ yrs) diversity abounds: openings where giants have fallen let in light to allow shrubs and seedlings to grow better, there is wood on the ground, standing dead snags, trees growing out of nurse logs, a mossy zone with perennials and groundcovers, a shrub layer, a lower understory tree layer, intermediate to very tall trees. This is all great from an ecologist’s perspective.

An oak woodland has a different character. If a woodland or savanna was burned, it might have an open character. If no fire killed the young trees and brush, it will be crowded with skinny trees reaching over each other for the light, maybe one or two legacy giants that were seedlings 150 to 300 years ago, overtopped by douglas firs; dappled shade, poison oak shrubs, and vines climbing the trees, grasses, a few shrubs (serviceberry, snowberry) and flowering bulbs (camas) and perennials (checkermallow, strawberries) persist in the low light. There will be dead standing oaks in either case, many with dead branches and brittle broken limbs among the live ones. And lichens: many species and a great biomass of lichens.

In a managed forest, the forester does the thinning in order to grow fatter trees for market, like a row crop. When these trees – all the same age – are eventually cut, like giant broccoli, there will be some green trees left and some dead standing snags because the Oregon Department of Forestry requires it.

Why? Why do we value snags enough to write them – however few and inadequate in number – into the forestry regulations? Life. And diversity. A dead tree has arguably more life in it than a live tree. The diversity of fungi, bacteria, and wood decay organisms is enormous. Beetles, termites, ants, and others feed on the dead wood and fungi. These are the base of the food web, the decomposers and recyclers that return nutrients stored over decades or centuries, to the forest.

There are plenty of birds (woodpeckers, chickadees, nuthatches) who visit the snag to find food, and excavate nest cavities in the softening wood. Others (owls, bats) who can’t excavate a hole, use those made by woodpeckers, in a grand circle of beneficial re-use and mutual aid. A dead tree is a great place for a raptor like a hawk or osprey to nest or sit and watch for prey, possibly a douglas or flying squirrel. Snags are so important to wildlife that getting rid of them endangers species that rely on old growth and dead wood.

Next time you drive through the Oregon Coast Range on the way to the beach, observe the difference between a national forest and adjacent tree farms owned privately or by the BLM. Instantly the trees get bigger in the national forest, the ground level cooler and more diverse, the depth of the canopy is higher and the light changes. Streams look like real streams. This you can tell at 55 miles per hour.

We had a tree next to the house made into a snag. A dougfir that needed to be removed for safety. Our arborist Brian French (that’s him up the tree in photo below) took off the limbs, topped it and crafted a new jagged top – an outstanding fake lightning strike to accelerate fungal invasion. (Final touch was a birdhouse built by birdman Tom Brewster, volunteer with the Yamhill Conservation District and local woodworker.) Brian also hollowed out a section of trunk behind a carefully cut piece of bark, then replaced the bark so the birds could move in right away without waiting for the snag to soften up.

Just in time for nesting season, a tree swallow pair scouted it and pronounced it livable. The rest of the flock looks on in envy. For the first time we have tree swallows careening over the house grabbing insects in the new, more sunny and open space. Yay snag.

Delving into mollusks, a little

I was cleaning logs for mushroom inoculation and I came across a large snail. The logs had been sitting around so I thought it might have taken refuge there after foraging on pots of seedlings nearby, as slugs do. My first impulse was to toss it out into the hot gravel on the driveway and let it fry (I know, so cruel. I regret these thoughts, right after they pop into my head).

On second and better thought, since it was tucked up in thick moss on a log that came from the woods, maybe it was a native from the woods and not one of the many invasives that plague our gardens. Turns out (thank you internet) it probably is a native forest snail, Pacific Sideband (Monadenia fidelis), but I should probably confirm that with an expert.

Three things I learned while keeping it in a dish: it moves pretty fast (for a snail), I left the lid off its prison for awhile so it would come out of its shell and had to peel it off the bottom of the bookshelf far below. It took a little over a minute to scoot over the side of this container when I started to photograph it. That and it poops a lot. At 30 mm across, it’s not small. It seemed livelier in the evening, so nocturnal?

From the most helpful field guides here and here I learned that it grazes on lichens usually, so I was right not to persecute it. Perhaps more thought-provoking is that it has several cousins or subspecies that are endangered or rare in Oregon, mainly because their habitats are threatened. They live in discrete regions and locations. The Columbia River is one region of endemism for snails, as it is for many plants and animals.

Since I wasn’t out looking for snails and the like, I might never have found this guy/gal (hermaphrodite) if I hadn’t handled logs for the mushroom project. The snail somehow survived its tree being chainsawed down and cut up into logs, and then tossed in a wheelbarrow, stacked, and cleaned. I am daily reminded of the diversity beneath our feet and how valuable and delicate it is.

I will probably have to collect a hard copy field guide for slugs and snails. I admit to a love of field guides. And I have many. One of my favorites is on oak galls – yes, an entire field guide packed with arcane information. I devour introductory chapters on how the animal or plant fits into its ecosystem, taxonomy, photos, fascinating life histories that others have spent whole lifetimes working out. If you like to go down rabbit holes of information, you can’t do better than a nice field guide.

I took the snail back out to the woods today, it’s probably enjoying a bite of lichen now before sleeping off the adventure. I’ll recognize it when I see it again.

Skinks in the rock pile

Earlier this spring I realized we had accidentally created some nice habitat for western skinks, an entertaining, exotic looking little guy with a beautiful blue tail. There was a lot of driveway gravel and random small rocks piled at the base of our crumbly basalt bank. I saw one weaving in and out of the rocks, and thought myself lucky to have a long look. Then I realized there was a second one, and they were playing hide and seek and chasing each other around, oblivious to me!! Ahh, spring.

According to Reptiles of the Northwest blue color in the tail is temporary – bright on juveniles, fading to grey or grey-blue in adults. I always see the blue tail disappearing in a flash. I have no idea how Alan St. John, author of the field guide, is able to capture them. But capture he does, and writes lovingly and entertainingly of skinks and other reptiles. A great read.

Weeks later I was gardening and flushed one out of the undergrowth. It immediately dashed for a rodent hole, but poked it’s head right back out again. We had a stare down, but the skink had the better skills, because if I looked away for one second, it would advance a centimeter and then freeze. I could not see it move, but there it was, inching forward. At the right moment it disappeared into the rockpile.

These guys are fast – like other lizards they can dash so fast that they can’t be caught, but are unable to keep up the pace, so their strategy is to dash, freeze, dash, and if all else fails sacrifice their tails, which can regrow if they are detached. The detached tail even wiggles to distract the predator while its owner gets away.

You can create habitat that snakes and other reptiles use by hollowing out a protected and dry place in a sunny area and covering it with stones and a little woody material. They will find the spaces beneath and this hibernaculum will be a refuge in the winter too for slug-eating garter snakes and others.